Scientists detect coral bleaching in Brazil – 04/12/2024 – Environment

[ad_1]

After months of extreme heat warming the oceans, researchers detected damage to corals off the Brazilian coast.

In the region of the southern coasts of Pernambuco and northern Alagoas, mass bleaching was observed, while in the south of Bahia a small portion of the colonies have been affected so far.

The phenomenon, which can lead to the death of corals, happens when the oceans spend several weeks with temperatures above average. Bleaching is one of the consequences of climate change caused by human activities, as most of the excess heat associated with global warming is stored at sea.

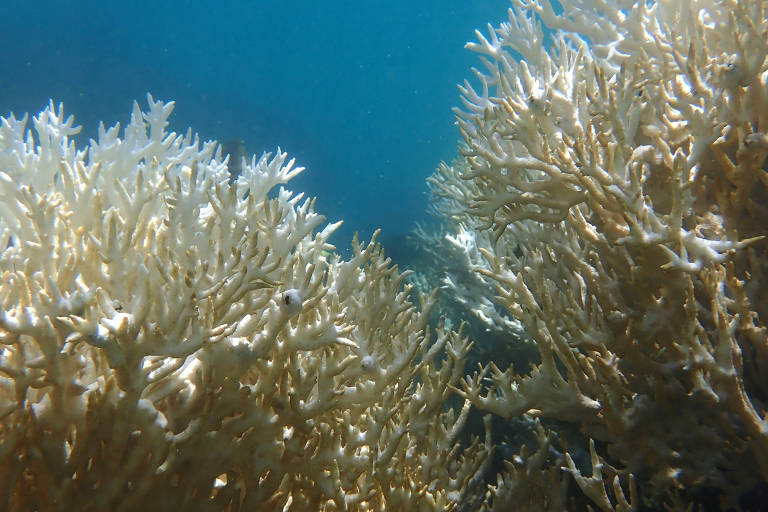

See before and after bleached coral on the Brazilian coast

Corals of the species Millepora alcicornis in Tamandaré (PE) in February 2024, still healthy, and in the following month, already bleached due to excess marine heat – Ágatha Naiara Ninow/PELD-Tams Project

In the Costa dos Corais Environmental Protection Area (APACC), a region between the municipalities of Tamandaré (PE) and Maceió (AL), several colonies were affected, according to Beatrice Ferreira, professor at UFPE (Federal University of Pernambuco).

She explains that mass bleaching is defined when around 50% of species or colonies in a large area are affected by thermal stress.

“The alerts started in March. Alert 1 went into effect and the bleaching of the most sensitive species really began”, he explains, referring to the alert scale used by Noaa (American Atmospheric and Oceanic Agency) in its satellite monitoring. From level 1 onwards, the agency considers it likely that there will be significant bleaching in the region.

In 2023, due to the heat records recorded in the seas around the planet, NOAA updated its scale, which until then had a maximum of alert level 2 (characterized by severe bleaching and likely significant mortality). Now, the methodology reaches alert level 5, where there is a risk of almost complete mortality of coral reefs.

“Not all species and not all colonies, but what has already been recorded here [na Costa dos Corais] —and I think that in a large part of the northeast coast, which has been on alert 1 or 2 for some time— there is mass bleaching”, says Ferreira.

The researcher has been studying the region for 30 years through the Tamandaré Long-Term Ecological Program, financed by CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development).

The species most affected on the Coral Coast, initially, was the fire coral Millepora alcicornis.

“Deducing from ours and other reports of ongoing work at APACC, we are reaching possibly more than 80% of the colonies of this species affected in the shallowest areas”, says the scientist. “Now, we already see that most species and colonies in shallow areas have been affected.”

On March 5, NOAA issued a statement warning that the planet was about to experience the fourth global mass bleaching event. Days later, the Australian government announced that the Great Barrier Reef is already being hit massively.

According to the country’s authorities, 75% of the Great Barrier Reef has already bleached and the Australian Marine Conservation Society states that, in the southern region, bleached corals have been seen at a depth of up to 18 meters.

The last global mass bleaching event happened between 2014 and 2017, when the Great Barrier Reef lost almost a third of its corals. Preliminary results suggest that about 15% of the world’s reefs have had high mortality rates.

Previous global bleaching events occurred in 2010 and 1998, years that, like 2024, were marked by the occurrence of El Niño.

Above-average heat causes corals to turn white because their color comes from colorful microalgae (also called zooxanthellae) that live in their tissues. Water that is too hot for too long causes these algae to produce a substance that is toxic to the coral, which expels them, leaving their limestone skeleton exposed.

A bleached coral is not dead — but it is weak and prone to disease. This is because the zooxanthellae, in a symbiotic relationship, provide essential sugars for the coral’s nutrition, produced through photosynthesis.

Therefore, the faster the sea returns to its usual temperature, the sooner that colony can recover the microalgae and once again have this source of energy. On the other hand, when heat waves are very strong and prolonged, the chances of mortality increase.

Brazil has the only coral reefs in the South Atlantic, concentrated mainly in the Northeast region.

The Abrolhos National Marine Park, in the south of Bahia, has so far not recorded as great an accumulation of heat as the rest of the northeastern coast, according to Noaa indices. Even so, some species even bleached.

“Until the end of March, in Abrolhos, there were few colonies of fire corals of the genus Millepora affected, as well as some of Mussismillia harttii“, says Rodrigo Leão de Moura, professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, who has been researching in the region for more than two decades.

“The prevalence was very low, below 5%, and the colonies were only partially bleached. In the north of Espírito Santo, the situation was even calmer, and we did not record any bleaching events”, he ponders.

Despite the good news, he says that the situation could still get worse if the heat continues to accumulate in the coming weeks. Furthermore, he explains that the repetition of episodes of thermal anomaly undermines the health of the corals.

“We have this idea that bleaching is episodic. In fact it is, and a large portion of the colonies — by 2020, the return rate [das espécies em Abrolhos] it tended to be more than 90%, so mortality was low—it comes back after such an event. However, in the long term, mortality is accelerating. Just because the coral turns greenish brown doesn’t mean it’s healthy,” says Moura.

The researcher adds that, over the decades, what has been seen is that more corals die than are born, which is leading to a decrease in coral cover.

In Abrolhos, six mass bleaching events were recorded: 1993, 1998, 2003, 2010, 2016 to 2017 and 2019.

The UFPE professor explains that, on the Brazilian coast, bleaching events occurred simultaneously across large areas, but with varying intensities in 1998, 2010, 2016 and 2019 to 2020.

In addition to the increase in global temperatures, the carbon released into the atmosphere by human activities and absorbed by the seas also causes the acidification of the oceans — which harms the formation of the limestone skeletons of corals and the shells of molluscs and crustaceans.

Scientists also highlight that the health of Brazilian corals is also impacted by the low quality of sea water, due to pollution and the inadequate granting of licenses for infrastructure works, such as dredging, and industrial facilities.

“In local communities, there are improvements [na conscientização sobre a preservação dos corais]. But we have not been able to overcome the chronic problems of sewage, coastal erosion and poor land use. We managed to move forward with the creation of protected areas, with better tourism and fishing practices, but not enough”, assesses Ferreira.

In terms of biodiversity, coral reefs can be compared to tropical forests: despite occupying only 1% of the Earth’s surface, these ecosystems are home to a quarter of all marine life.

This Wednesday (10), BNDES (National Bank for Economic and Social Development) launched a call for proposals for up to R$60 million for projects to protect coral reefs in Brazil.

The bank will prioritize initiatives to improve water quality, combat exotic species and predatory fishing, tourist planning and mapping, maintenance, monitoring and protection of corals.

[ad_2]

Source link